Miles Davis

“I can’t talk about Miles Davis—he’s Miles Davis!” The assignment was to talk about people we admire and explain what makes them great. I didn’t think everyone in the group at Patterns—designers, entrepreneurs, and film people—wanted to hear me prattle about Jazz for a week, so I tried to think of some heroes that weren’t musicians.

I couldn’t. I was going to talk about Miles Davis. I was conflicted about presenting him as a hero. I worried about mythologizing a gruff drug addict into a saintly genius. Still, one has to separate the person from the work.

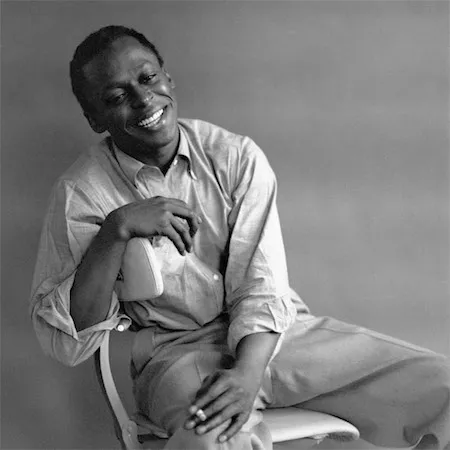

After sharing my thought process with the group, I pulled up a Google Image Search for Miles on the TV, looked at it for a few seconds, and said: “Just look at this motherfucker. Miles Davis epitomizes cool.”1

“Just look at this motherfucker.” Photo by Paul Talumbo.

Then, I told some stories.

I told them that when Miles first moved to New York City, he looked for the baddest cat around, which at that time was Charlie Parker.2 Miles started to hang out with Bird, and ended up playing in his group—and probably picking up the heroin addiction from him too.

I said that Miles could pick the right people for whatever idea he had in his head, and then knew to let them do their thing without much instruction or rehearsal.

I gave some examples of the way Miles changed the music, such as the cool jazz aesthetic in the wake of the fast, frantic style of bebop. I explained that the first quintet still defines the repertoire of straight ahead jazz today, and that the second quintet is probably more influential than any other group on the way we play today, 50 years later.

I explained how, when electric music and rock ‘n’ roll and funk became popular in the late 60s, Miles embraced it and made wild, funky electric music. This was especially relevant for Patterns as we had been exploring the effect of technology on the creative fields.

I was encouraged to see people around me nodding in interest and recognition as I talked about Jazz. I shared my worry about mythologizing our heroes. I love Miles for his creative output, not for his personality. He was a promiscuous drug addict and often took credit for tunes he didn’t write. I’m interested in the biographies of artists I admire, but I’m a lot more interested in their work.

Suggested listening

Given that Miles Davis put out 48 studio albums and 36 live albums3, and that I haven’t heard most of them, this list is in no way comprehensive. But it should give the newbie a taste for the diversity of the music and some direction for further exploration. The best way to get into Jazz is to find something you like, look up the artists, and see what else they did. That’s how I started, and I’m still going strong.

Birth of the Cool

A compilation documenting a nine piece group that recorded in 1949 and 1950. Considered paradigmatic for the so-called cool jazz subgenre, the band featured colorful, orchestral-ish arrangements by Gil Evans that are informed by the “hot” bebop style of the 1940’s but mark an important departure from it. This music is noticeably more chilled out and more accessibly melodic than bebop, which perhaps requires a greater understanding of Jazz to be appreciated.

The first quintet

Around 1956, Miles assembled what would be known as his first great quintet, with John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Philly Joe Jones on drums. My favorite albums of this group all came from the same recording session in 1956: Relaxin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet, Steamin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet, Cookin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet, Workin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet. They’re all awesome, and Jazz cats all over the world still play a lot of the same tunes in the same keys because of these records.

Kind of Blue

Supposedly the best selling Jazz album of all time and the first Jazz album I ever heard. I’m not sure how it became so well known, since they made plenty of great albums around this time, but it sure is good. The players are Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Paul Chambers, Jimmy Cobb. Wynton Kelly subs in for Bill Evans on piano for Freddie Freeloader.

The second quintet

Miles’ second great quintet had Wayne Shorter on tenor saxophone, Herbie Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on bass, and Tony Williams on drums.4 The influence of this band on Jazz musicians cannot be overstated. Collectively, we fucking love this band.

There are six studio albums by the quintet and numerous live recordings. They played mostly original compositions in the studio, and mostly standards on the road.

Going electric

The first Miles album to include electric instrument is also the last album to feature the second quintet intact: Miles In The Sky, recorded in 1968. Miles’ fusion truly began with In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew, released in 1969 and 1970 respectively.

And beyond

Miles’ career didn’t end in 1970. He took a six year hiatus starting in 1975, but otherwise continued to play until his death in 1991.

Miles Davis in 1991. Photo by Peter Buitelaar.

Footnotes

-

I’ll admit that although I was mostly speaking extemporaneously, that move was planned. ↩

-

Charlie Parker, known as “Bird”, created the style called bebop. ↩

-

According to Wikipedia. Not counting bootlegs, unauthorized releases, etc. ↩

-

Early iterations of the quintet had George Coleman or Sam Rivers on saxophone, but the group didn’t become truly great until Wayne joined in 1964. Just my opinion—although the stuff with Coleman and Rivers is really good too. ↩